The idea of ruins — archaeological, architectural, cultural, even psychological — lies at the center of Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City, published in November 2017 by Temple University Press; it’s a philosophical meditation masquerading as a coffee table book.

The idea of ruins — archaeological, architectural, cultural, even psychological — lies at the center of Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City, published in November 2017 by Temple University Press; it’s a philosophical meditation masquerading as a coffee table book.

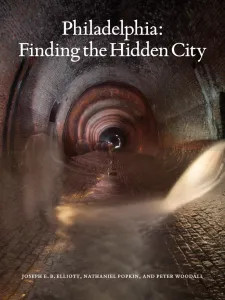

A handsome book it is, too. Photographer Joseph E.B. Elliott provides contemplative perspectives on a variety of public, semi-public, and commercial spaces in Philadelphia, many of them off-limits to the casual flâneur in the City of Brotherly Love; the accompanying text, by Nathaniel Popkin and Peter Woodall, eschews a straightforwardly historical approach by considering the relationships between these spaces, their history, and their current uses and disuses.

Most books of Philadelphia history like this, boasting glamorous and unpeopled photographs of interiors and restored exteriors, concentrate on the colonial and early national eras of the 18th and early 19th century. The Hidden City authors turn their attention instead to the later 19th and early 20th centuries, finding the objects of their contemplation in churches both formal and informal; sewers and abandoned subway stations; municipal buildings, some like Philadelphia’s City Hall still abuzz with activity and some like Germantown’s Town Hall in disuse; and prisons like Eastern State and Graterford, designed on the long-abandoned idea of the panopticon as a means of moral punishment.

The “ruin” in this book, though, is considered less as an attractive fragment than as a living object with a life of its own. “For Philadelphia seems to possess an exceptionally large number of places that have disappeared elsewhere — workshops and small factories, sporting clubs and societies, synagogues and theaters and railroad lines — like endangered species that have managed to stay alive in some remote forest or swamp,” Popkin and Woodall muse. Among the more telling passages are a visit to the remains of the International Peace Movement community that Bible-thumper Father Divine founded, along with the Divine Lorraine Hotel on North Broad Street; the Church of the Gesú, site of a depressing and violent civil rights controversy in the 1940s; and a peek into the John Stortz and Son tool factory, founded in 1853 in Philadelphia’s Old City and, somewhat miraculously in this day and age, still flourishing and providing employment to machine workers and small craftsmen. An additional pleasure of the book is a long-overdue consideration of the monumental contributions that people of color and women made to the economic and cultural life of the city over the past 150 years.

As Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City peels back the layers of the past, it reveals more than ruins of buildings; it also reveals the ruins of certain habits of mind, of shared community values, reminders of the stresses and anxieties that made and continue to make Philadelphia a unique place in the world. Film directors like Terry Gilliam and David Lynch turned some of these same settings into nightmares, but that didn’t do them justice. The book gives them a new and glowing life. Every city has a different flavor, hard to define precisely and, because cities are always changing, always provisional. Philadelphia: Finding the Hidden City is an essential bridge between past and present. Sure, it belongs on your coffee table. But make sure to read it, too.

NOTE: The book is the product of the ongoing Hidden City Philadelphia project; you can find its website here.