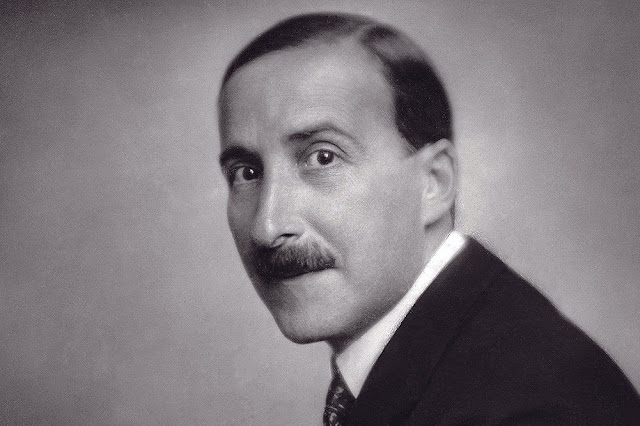

From Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday (1942), translated by Anthea Bell:

In fact, it must be said in all honesty that a good part, if not the greater part, of all that is admired today in Europe and America as the expression of a newly revived Austrian culture in music, literature, the theatre, the art trade, was the work of the Jews of Vienna, whose intellectual drive, dating back for thousands of years, brought them to a peak of achievement. Here intellectual energy that had lost its sense of direction through the centuries found a tradition that was already a little weary, nurtured it, revived and refined it, and with tireless activity injected new strength into it. Only the following decades would show what a crime it was when an attempt was made to force Vienna — a place combing the most heterogeneous elements in its atmosphere and culture, reaching out intellectually beyond national borders — into the new mould of a nationalist and thus a provincial city. For the genius of Vienna, a specifically musical genius, had always been that it harmonised all national and linguistic opposites in itself, its culture was a synthesis of all Western cultures. Anyone who lived and worked there felt free of narrow-minded prejudice. Nowhere was it easier to be a European, and I know that in part I have to thank Vienna, a city that was already defending universal and Roman values in the days of Marcus Aurelius, for the fact that I learnt early to love the idea of community as the highest ideal of my heart. (44-45)