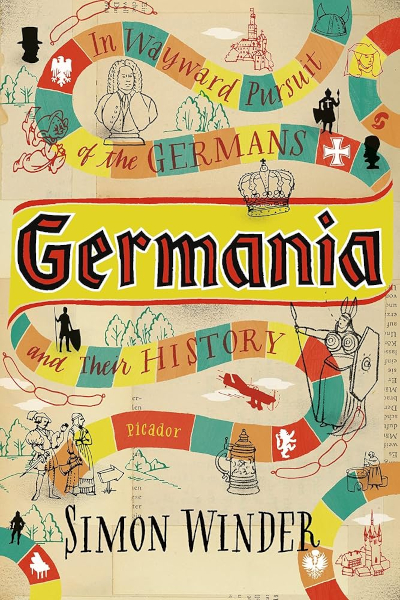

From Simon Winder’s delightful 2010 book Germania: In Wayward Pursuit of the Germans and Their History:

Quite possibly the pleasure of this way of life would be much reduced in some other countries, particularly more insistently gregarious places such as Italy. German culture puts a high value on temporary solitude of a stagey kind. Perhaps this is its great gift. In some moods I think there is no need to do anything other than read German writers from the first half of the nineteenth century — a sort of inexhaustible storehouse of attitudes flattering to those who just like sometimes to be left alone. …

The poetry on this subject stretches out to the most hazy, distant horizon and fed a century of German songs, culminating perhaps in the greatest of them all: Mahler’s setting of a Rückert poem, “I have lost track of the world with which I used to waste much time,” a work of such richness that it can only be listened to under highly controlled circumstances. The idea, whether in Goethe, Mörike, Rückert or Heine, is to be alone, in a wood, on a mountain, in some overpoweringly verdant garden, or just inside one’s head, almost always as a moment’s pause before plunging back into a world of love and normal human decisions. This tic is of course a bit unpolitical and some writers have seen it as passive in a way that implies a German malleability and failure to engage with disastrous implications for the future. But equally it is an anti-political, fiercely private stance, with a built-in resistance to fanaticism or mass manipulation. It seems hard on Schubert’s songs for them to be viewed as early danger signs of a failure to stand up to Nazism.