As we await history’s verdict on the events of the past week or so, we look forward to the next exhibition at New York’s Neue Galerie, Neue Sachlichkeit/New Objectivity, which opens at the Fifth Avenue museum on February 20. Running through May, the show, curated by Dr. Olaf Peters, who also curated the Neue Galerie’s fine Otto Dix and Degenerate Art exhibitions, throws a spotlight on one of my favorite artistic periods and celebrates the 100th anniversary of the groundbreaking 1925 exhibition curated by Gustav F. Hartlaub at the Kunsthalle Mannheim. (I note also that many of these artists were cited as “favorites” by R. Crumb, who shares not a few affinities with them.)

“Characterized by its critical realism, social commentary, and detailed depiction of contemporary life, and marking a significant departure from Expressionism’s emotional intensity … [the] Neue Sachlichkeit movement was divided by two philosophies — the unflinching and socially critical Verists, and the Classicists, who focused on harmony and beauty,” says the Neue Galerie:

The show will offer a wide-ranging perspective, exploring the tension between the Verists and the Classicists, which will be illustrated through a multidisciplinary installation, featuring paintings, sculpture, photography, decorative arts, works on paper, and film. … The presentation interprets these two camps as a coherent chapter in art history, focusing on the ways that the New Objectivity proponents mirrored the Weimar Republic’s cultural, political, and social complexities.

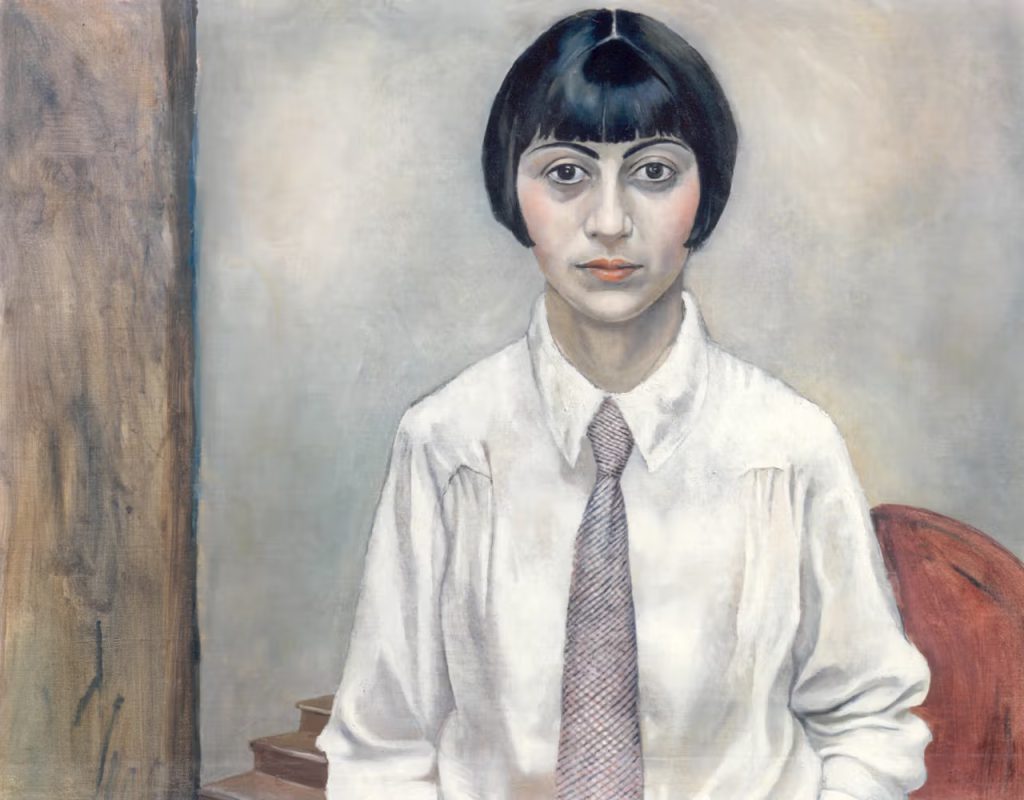

There may be no better time to reacquaint yourselves with this remarkable body of work; central to the art was the idea of the integrity of the individual, especially in an era of fluid gender presentation and representation (as evidenced by Schlichter’s Woman with Tie at the top of this item). Needless to add, the movement was crushed by Hitler’s seizure of authoritarian power in 1933; I tend to side with Peter Gay who saw this as a “Revenge of the Father,” as he put it in his 1968 book Weimar Culture, also worth a rereading. Indeed, why not read that, then enjoy the exhibition? It opens on February 20; tickets (which will be hard to come by, no doubt) are now available here.