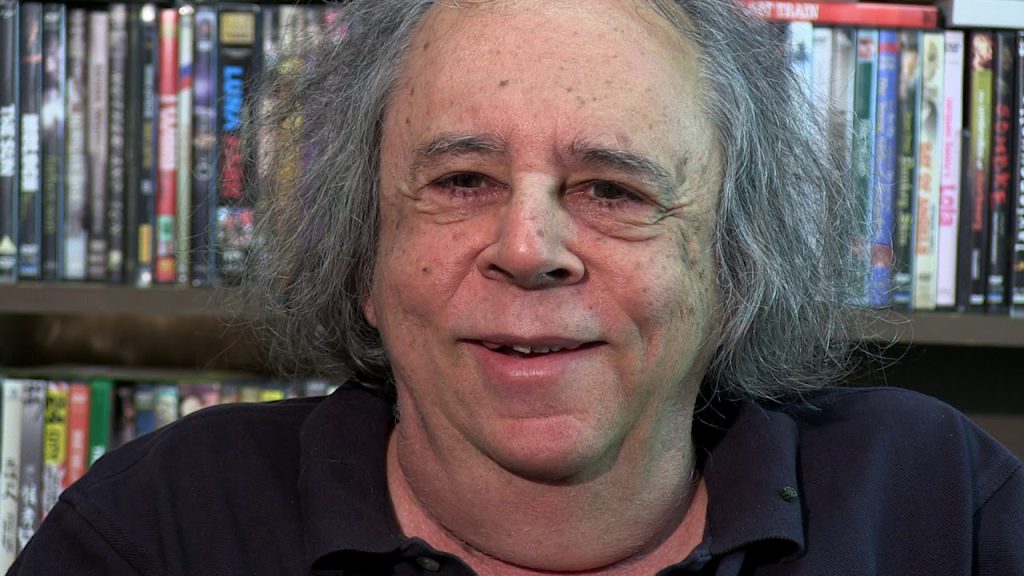

One night in 2003, I showed up at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery for Panic! (How to Be Happy!), that year’s offering from Richard Foreman. The year before I’d first visited the theater for Maria del Bosco and written — quite enthusiastically, I suppose — at my blog about my experience. But on that 2003 occasion I went to the box office to pick up my tickets; standing next to it were Foreman (instantly recognizable — rumor had it that he’d been in the running for the role of Mary Wilkes’ ex-husband, the “homunculus,” in Woody Allen’s Manhattan, a part that eventually went to Foreman’s downtown playwright colleague Wallace Shawn) and his wife, Kate Manheim. When I mentioned my name to the box office manager to retrieve my tickets, Foreman walked over to me and said, “I’ve been waiting for you! I’m Richard Foreman. I really appreciate what you’ve been writing about my work.”

To say I was flabbergasted at this would be to understate my reaction, but as I came to know Richard over the following years, I came to realize that I was no exception. I mean, why should he care what I wrote? I was no academic, nor was I a member of the professional critical class — I maintained a modest little blog, for crying out loud. But among his most memorable qualities — he shuffled off this mortal coil just this past Saturday, January 4 — was a generosity, kindness, and acceptance of the human condition that affected all those who knew him.

Over the years that followed, I wrote more about Richard’s work, following up on my early enthusiasm for his production of The Threepenny Opera at Lincoln Center in 1976. (That same day, in the afternoon, I saw Gielgud and Richardson in the New York premiere of Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land. That was quite a Saturday.) A trip to the Drama Book Shop then rewarded me with his first collection, Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos (New York University Press), which had just been published and a copy of which is at my side as I write this.

I saw most of Richard’s work that followed Maria del Bosco; we met infrequently but always pleasantly for coffee and conversation after that; he was kind enough to attend the premiere of one of my own plays a few years later, followed by his enthusiastic approval; we casually discussed the possibility of my writing some kind of biography of him — a project that, thankfully for both of us, never panned out; and even today the home page for his Ontological-Hysteric Theater memorializes a 2015 celebration of his work that I moderated with Richard and his long-time friend, filmmaker Ken Jordan. I never really recovered from that initial excitement of our first meeting, and I recall the near impossibility of “moderating” such an entertaining, self-effacing raconteur.

(I also remember talking to Richard about my attending one of his productions; I told him I’d try to do so on the date he suggested, but it all depended on whether I could get a babysitter for my two young children. “Bring the kids!” Richard said. “Children love my plays!”)

My writing about Richard’s work was an attempt to come to terms with his extraordinary sense of the possibilities of theater for the individual consciousness. As a writer — as any writer, I suppose — I felt the need to articulate just what it was in my experience of the world that led me to my own reaction, and this included my experience of Foreman’s constructed theatrical world.

What made his theater so special and revolutionary was his attempt to undermine every single moment of a traditional theatrical experience, from character and plot to light and sound, to radically disorient the spectator, throwing that spectator back on his or her own emotional, intellectual, and spiritual resources. What a character said violently contradicted what a character did; stasis would be interrupted by physical, visual, and aural dance and chaos; and all of this was centered in the experience of the live human body, speaking, singing, dancing, and talking. As Foreman sat, Godlike, on a throne held together by duct tape during the performance, cuing light and sound himself across a phantasmagoric, P.T. Barnum-style spectacle of wavering perspective, he was never really in control, just as we’re never fully in control of the world as it presents itself to us.

All of this was in the service of sensual liberation: to perceive the world anew, and to realize that the world was what we made of it as individuals. Throwing off the shibboleths and cliches of a constructed world made for us by religion or politics or corporations or tradition, we were encouraged to make a world for ourselves. Needless to say, for Richard, this had — or, at least, could have — profound political, social, cultural, and sensual consequences for every single spectator. If 100 people sat in his theater watching Maria del Bosco, they saw 100 different plays; the same could be said for any play, I suppose, but that truth was never at the center of the deliberate aesthetic program as it was for Richard.

This was a profound challenge not only to the theatergoer, but the critic too, and everybody else. Our success or failure at meeting this challenge was entirely up to us. Of course, Richard himself put it best, in his Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater:

But I want a theater that frustrates our habitual way of seeing, and by so doing, frees the impulse from the objects in our culture to which it is invariably linked. I want to demagnetize impulse from the objects it becomes attached to. We rarely allow ourselves the psychic detachment from habit that would allow us to perceive the impulse as it rises inside us, unconnected to the objects we desire. But it’s impulse that’s primary, not the object we’ve been trained to fix it upon. It is the impulse that is your deep truth, not the object that seems to call it forth. The impulse is the vibrating, lively thing that you really are. And that is what I want to return to: the very thing you really are.

I have only to add that Richard changed my life — as he changed the lives of so many others — and that I’ve looked at the world differently since being exposed to his plays and his person. A glass raised, then, to his memory.

Below is a collection of my writings about Richard and his work that I put together not long ago.