I spent several pleasant hours this holiday weekend with Putting the Record Straight, a 1981 memoir by John Culshaw, the legendary Decca Records producer who oversaw many of the great postwar opera recordings. His autobiography begins with his years as a soldier in World War II and takes him through his career as the manager of the Decca Record Company’s classical division from 1956 through 1967; after this, he was the director of musical programming at the BBC through 1976. Culshaw had written about just before the end of his career at Decca before he died prematurely in 1980 at the age of 55, leaving Putting the Record Straight unfinished. Fortunately the manuscript was nearly complete, and Culshaw’s colleague Erik Smith was able to bring it to publication.

Culshaw, who was awarded an OBE in 1976, had very little musical talent of his own and far-from-perfect pitch; the early chapters of the book focus on his own self-education in classical music as he flew wartime missions over the continent. After he wrote an early study of Rachmaninov, he joined Decca, and like most opera memoirs there are delightful stories of Georg Solti, Birgit Nilsson, Herbert von Karajan, and others through the post-war years, not to mention the birth of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and the recording of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem. Unlike many opera memoirs, however, Culshaw focuses on the business and technical end of the classical music industry, describing the debut of the LP and stereo recording techniques with considerable good humor and fascination, providing an entertaining answer to the question, “Just what is it that classical music producers do, anyway?”

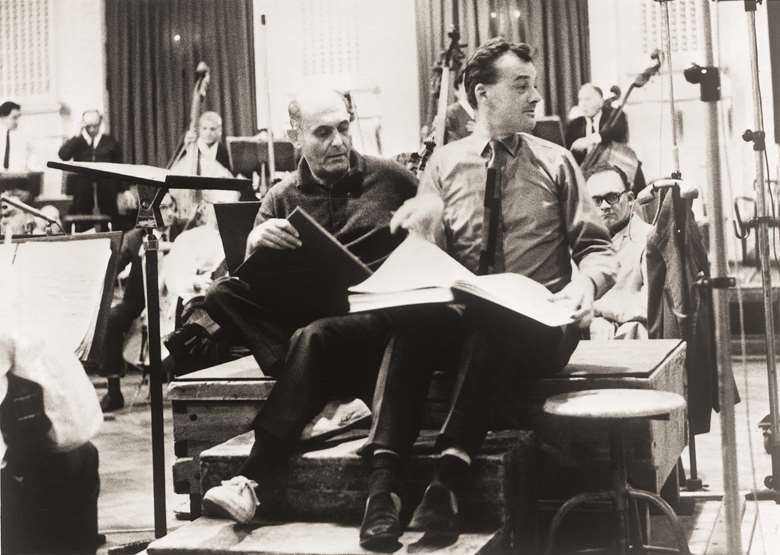

Of course, Culshaw may be best known for producing the great Solti Ring cycle in the 1950s and 1960s, the first in stereo and still a landmark in recorded sound. (Culshaw described this experience at length in his memoir Ring Resounding.) When I purchased a starter audiophile setup a few years ago, the first recording I purchased was the first pressing of Das Rheingold. It doesn’t begin to compare with digital remasterings of the recording which rob it of its warmth somehow; the difference is evident from the first bars of the opera, which even at a relatively low volume set my floor vibrating, unlike its digital siblings. The cycle hasn’t been out of print since its release, but it’s only been remastered for CD and streaming.

Until now, that is. As I was preparing this post, I came across news that Decca was remastering the original tapes of the project for vinyl once again. Described as a “high-definition transfer of the original master tapes” in something called Dolby Atmos, the Decca Classics release follows a restoration of these tapes. The vinyl albums are being published piecemeal, the first being Das Rheingold, which was released earlier this month, the others to follow in the new year. At these prices, I’m not sure I’ll be giving up my used copies quite yet, but once I hit the lottery I think I’ll have to get my pre-orders in.