A few more items from the cupboard, these concerning cartoonist Christoph Mueller and published here a few years ago.

Originally published on March 4, 2020

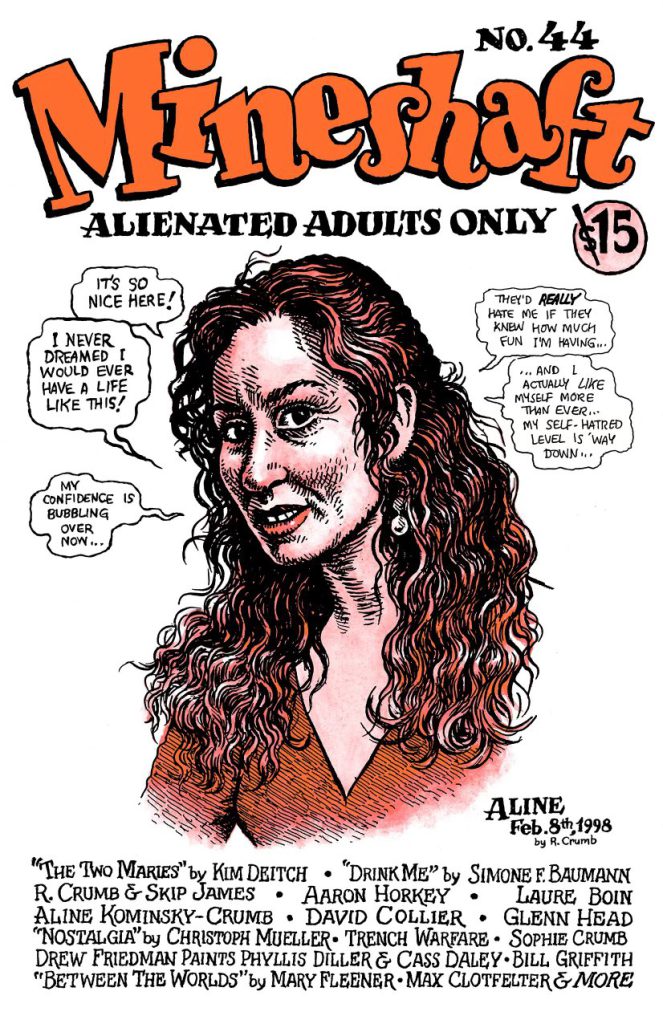

I’m in receipt of The Mighty Millborough, a fine self-published portfolio of work by Christoph Mueller, currently of Germany. I first came across his comics in Mineshaft and quickly sought out more.

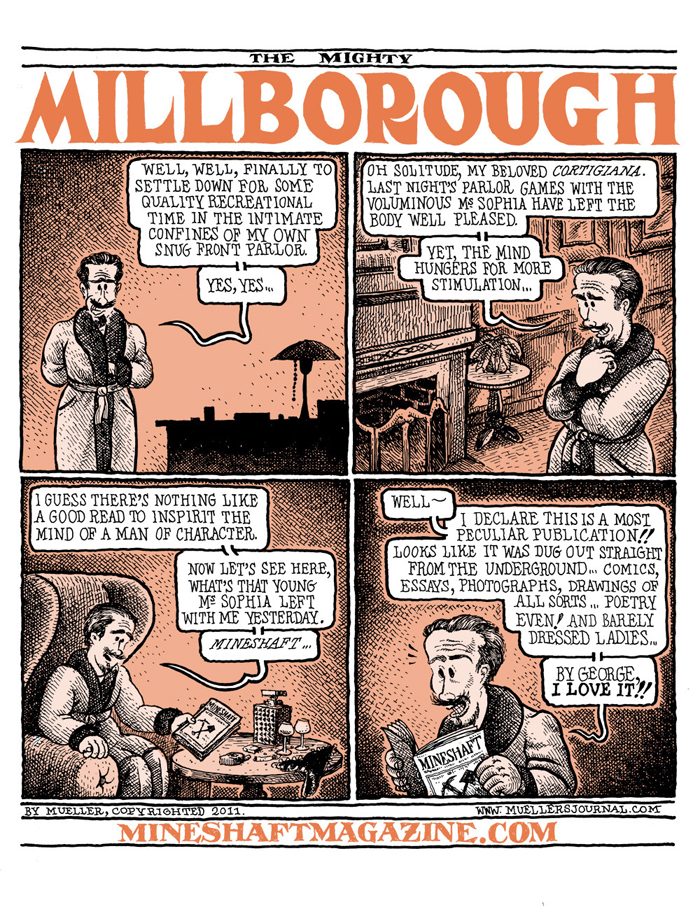

Mueller’s elegant, carefully crafted comics seem simultaneously nostalgic and unsettling, an evocation of the mirrored images of the individual and the world. His Millborough comics are a study in isolation, solitude, and cynicism set in Sassafras County, an idealized small-town America of the 1930s. The main character’s name itself was inspired by the old-time-radio situation comedy The Great Gildersleeve, but Mueller’s absurdist, quotidian approach is even more reminiscent of Paul Rhymer’s great neglected Vic and Sade radio comedy of the same period.

The cartoonist’s craft is evident in every panel; a post-Crumbian attention to detail and careful, almost melancholy crosshatching lend contemplative depth to his backgrounds and, especially, his domestic interiors. Millington F. Millborough’s house, which boasts a warm if dark “Library of Drink,” is a textured expression of the character’s own interior life. But whereas Crumb’s characters explode with anxiety, Mueller’s bottle it up inside (an apt construction, that), and more frequently than not, that anxiety like Crumb’s is sexual.

It so happens that I share many affinities with Mueller and his work, not least an admiration of W.C. Fields and especially It’s a Gift. I’m only partway through the portfolio and may have more to say. You can read more about his work at his web site.

Originally published on June 24, 2020

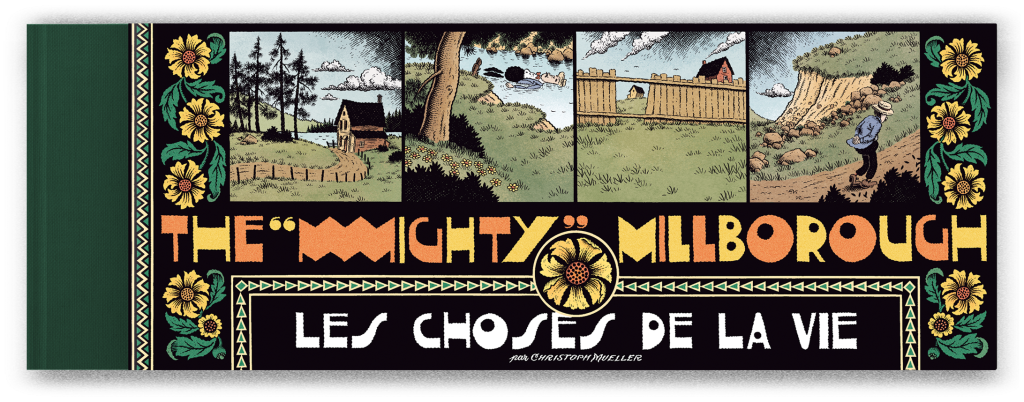

Christoph Mueller‘s The “Mighty” Millborough: Les Choses De La Vie, published by 6 Pieds Sous Terre just last year, collects over a hundred of Mueller’s adventures of the contemplative isolate Millington F. Millborough, resident of Sassafras County in the 1930s. A polite middle-aged bachelor with a taste for drink, Millborough spends quite a lot of time alone, a solitude that leads him to contemplations about landscape and his place in it. “Some feelings words cannot express,” he muses, meditating on a hilly New England landscape. “Nor music, art or act — only landscape can.” Indeed, a great deal of Les Choses De La Vie considers how the man makes the landscape, and the landscape makes the man.

Mueller’s style seems the unholy love child of Little Nemo‘s Winsor McCay and Mutt and Jeff‘s Bud Fisher — backgrounds are lavishly detailed, and his human figures are vaguely ridiculous against it, especially Millborough’s, traipsing through Sassafras County with cigar in hand and lost in self-conscious thought. Of course, it’s this self-consciousness that renders Millborough ridiculous, if sympathetic; it’s the artist who draws character and background together, not the character himself. Although Millborough doesn’t have much luck with the modern world — his battle against automobiles especially is doomed to comic failure — he nonetheless values man-made architectural elegance and grace (more obvious in an earlier, full-color portfolio of Millborough’s adventures). The natural landscape in Millborough’s eyes is prone to surreal transfigurations, as is Millborough’s body in that landscape, the McCay influence; the comic loping bodies of the strip’s characters are straight from Bud Fisher. Millborough’s friends respect him if they don’t understand him — maybe a degree of tolerance we’ve lost in contemporary America, as we’ve lost valuable Millboroughs themselves. Mueller reminds us of what we’ve lost with them.

The “Mighty” Millborough: Les Choses De La Vie has no American publisher, alas, but is available from the French publisher here. It is a gorgeously made collection, inside and out. Pester your American publisher friends, please, about Mr. Mueller’s “Mighty” Millborough.

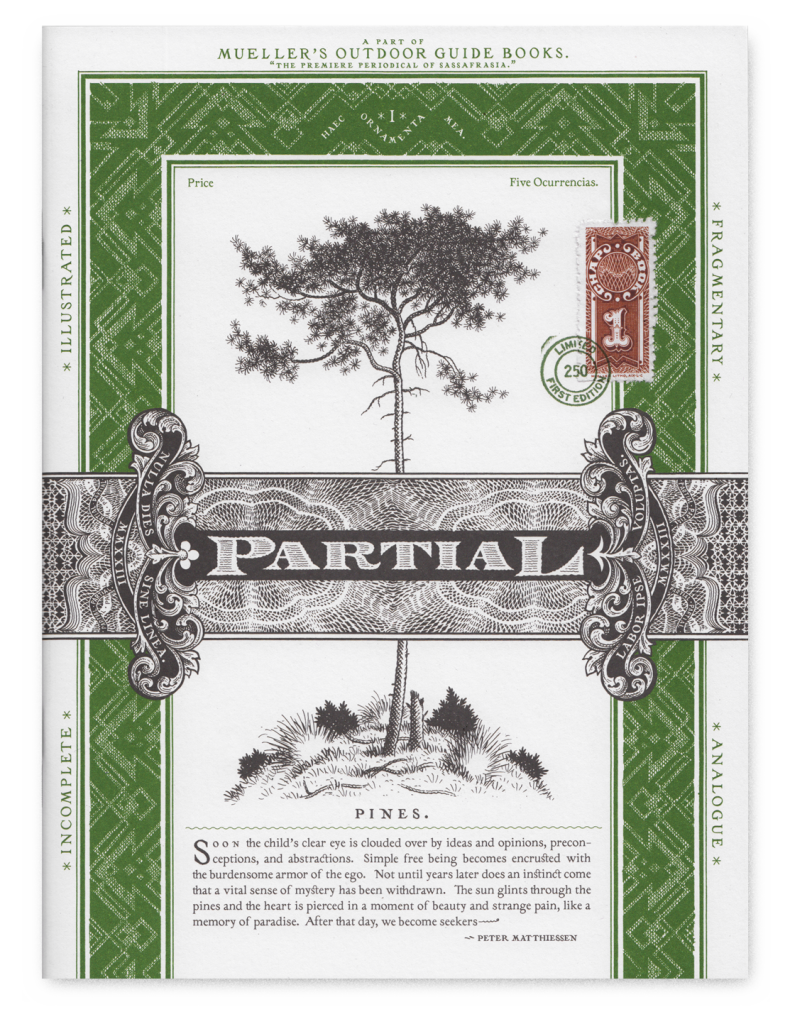

And an appreciation by the brilliant Chris Ware:

I believe him to be one of the most talented young cartoonists in Europe, and easily one of the most sensitive hand-lettering typographers in the world. I might be wrong about this, but European cartoonists seem to view the world and the self from the top down, or the outside in, whereas Americans seem to try to see from the inside out. Christoph seems capable of both. As well, there are few cartoonists, European or American, who have taken the incandescent example of Robert Crumb — the original inside-out cartoonist — and folded it into their own approach and sensibility so sensitively, self-critically and, most important of all, so warmly, than Christoph. He’s a careful observer and attentive draughtsman, and his sensitivity to craft and to turn of the century (i.e. the 19th to the 20th century) typography and ornament, back when the human hand still obviously contributed something to the world we see, is pretty close to unparalleled. He seems to understand letterforms the way botanists understand plants: where to sow them, how to shape them, and most especially, how to make them grow. Of all human hands, Christoph’s is one of the more elegant and sensitive I know.