A few weeks ago I encouraged donations to radio klassik Stephansdom, a cultural German-language radio station in Vienna which is in some financial distress. The station manager, Christoph Wellner, was kind enough to ask me to provide a short message in support of their campaign, and I did so without question — in English, however. It was broadcast this morning as part of their fundraising effort, and you can listen to it here; my little offering begins at about the 9:30 mark. (Click on the “Sendung nachhören” to start the program and hear my clarion cry to Vienna.) I’ve always wanted to be a classical music station program host, and given the few openings for such a position, this will be the closest I come, I suppose.

I’ll just take this opportunity to encourage you once again to support radio klassik Stephansdom, for all the reasons I mentioned in my statement. You can do so here. Tell ’em I sent you.

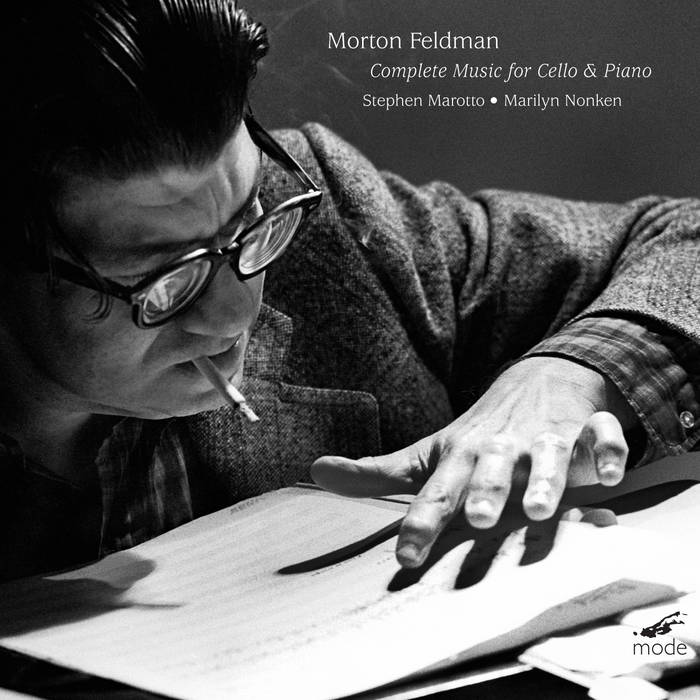

It’s taken a while, but it’s worth the wait: the

It’s taken a while, but it’s worth the wait: the